Paul Darlington

Forty years ago, at 05:30 on Tuesday 1 May 1984, Bill (Willie) Taylor, a signaller at Carlisle Power Signal Box (PSB) realised that 4S55, a Liverpool (Garston) to Glasgow (Gushetfaulds), a freightliner train had become divided south of Carlisle and both portions of the train were rolling downhill towards Carlisle Citadel station. It was carrying dangerous, highly explosive chemical goods, including toxic tetraethyl lead compound – the treatment used in leaded petrol – and 750 bags of oxalinic acid. Using all his knowledge and experience, Bill quickly and calmly switched the uncoupled wagons onto the empty Carlisle Goods Avoiding Line, avoiding disaster.

Sadly, Bill passed away the following year, before his son David Taylor joined the railway. RailStaff recently met up with David, now account director at Thales, to hear of his recollections of Bill and the incident 40 years ago.

The incident

The train had stopped earlier at Preston with dragging brakes. Usually, a fully air-braked train which becomes divided breaks the air pipe between the vehicles, causing the brakes on both portions to activate and bring both to a halt. So why didn’t this happen? The train received attention at Preston, but after closing the air brake cocks half-way down the train and rectifying the problem, the cocks were not reopened. From that moment on, disaster was inevitable as the front of the train was fine but the rear was unbraked.

Another problem, it is believed, is that the screw couplings between wagons 5 and 6 were not stowed away properly and were left swinging. It is thought that the rear brakes were still dragging when the train left Preston, but gradually the brakes on the rear vehicles ‘leaked off’ and by the time the train reached the Fells the train was running freely. However, because the gradient as far as Shap is almost all rising, the couplings between wagons 5 and 6 were kept tight.

Once over the top at Shap Summit, the coupling between wagons 5 and 6 probably went slack and the swinging coupling struck an AWS magnet in the four-foot and was lifted upwards. A damaged magnet was believed to have been found later. The train coupling came off the draw hook so that the rear 10 wagons, with their dangerous cargo, were now free running and unbraked.

The rear 10 wagons of the 15-wagon train were initially left behind, but then started to gather speed on the downhill grade towards Carlisle. Bill spotted the irregular indications on his panel and realised he had a divided runaway train, and that he only had moments to act. He was also aware that there was a passenger train in the station at Carlisle. The locomotive and the front part of the freight train which were still coupled were allowed to run forward safely into Carlisle station and signalled to a stop. After seeing that the leading part of the train had passed Upperby Bridge Junction, Bill switched the points to divert the runaway portion onto the freight-only line bypassing the station.

The rear divided wagons negotiated the sharp curve under Nicholas Bridge at Carlisle and thundered under the WCML and Maryport rail bridges, and over Bog Junction and Rome Street Junction at an estimated 60-70mph. A 20mph goods line restriction had already commenced at Upperby Bridge Junction. The runaway made it around the sharp right curve onto Denton Holme Bridge where the wagons crashed through the bridge and into the River Caldew. The two leading wagons came to a rest, derailed and badly damaged, about 50 metres on the north side of the bridge where Denton Holme South signal box had once stood. At 05:42 the residents of nearby houses were awakened by the loud crash and were soon gazing over the wall at the wreckage in the river. The bridge was pushed off its bearings into the river and a 60-foot piece of rail was hurled into the end of one of the containers.

Just doing his job

There was significant wreckage with much of the train in the river, but thanks to Bill’s quick actions to minimise risk to the public and rail staff, nobody was hurt. Local residents were evacuated for a time and it took weeks to clear up the wreckage.

The UK’s largest crane had to be brought in to lift the containers out of the river, and locals were even invited on a coach trip to Blackpool to clear the area whilst particularly difficult crane lifts were carried out.

A video on YouTube shows all the 1984 TV news coverage of the derailment, including interviews with Bill, where he says he wasn’t a hero and was only going his job. He also says that he would do exactly the same thing again if required, and he would be back at work that night.

Bill also later said: “There was little time to discuss what would be the best course of action – I knew there was going to be some form of incident whatever action was taken, but the lesser of the two evils was to divert the runaway away from the station, protecting the station and Carlisle city centre”.

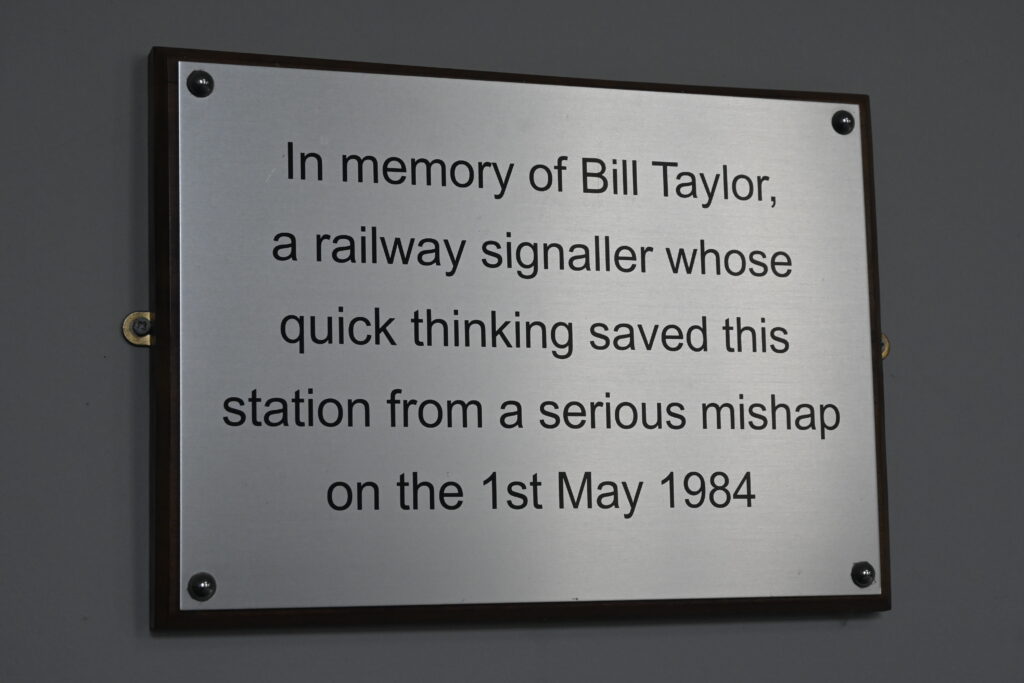

David is immensely proud of his father and, with his brothers and sister (Ian, Michael, and Margaret), had previously been involved in unveiling a plaque to the memory of Bill in a Carlisle station waiting room. David explained that Bill had started his railway career as a ‘knocker up’ moving on to be a ‘box lad’ booking train movements. He became a relief signaller and worked at most of the 46 mechanical signal boxes in the Carlisle area. It is believed he retrained as power box signaller at Kingmoor PSB before transferring to Carlisle PSB when Kingmoor closed in 1973. Outside of rail, Bill was an accomplished violinist with several local country and western bands, a very skilled model maker, and the proud father of five children.

Counselling

The incident happened years before today’s post incident counselling and therapy processes were put in place. So, after the incident on the 1 May 1984, Bill finished his shift as normal and on his way home stopped on the banks of the River Caldew to look at the train wreckage and demolished bridge. David remembers coming downstairs to find his dad at the breakfast table looking calm, but thoughtful and shaken. David went to school wondering what had actually happened, only to come home to find his street full of press and TV news reporters, and to learn that his dad was the hero signaller (signalman in those days) of Carlisle.

It is worth considering that Bill was 58 at the time of the incident and had spent over 40 years working as a signalman in both mechanical and power signal boxes. Signallers have to remain calm and to concentrate at all times. They have to know and apply the operational rules ‘to the book’, hour after hour, day after day. But in the event of an incident such as Carlisle in May 1984, they must think quickly and calmly put control measures in place.

Bill certainly had to do that and, having worked for the railway for 44 years, he had seconds to decide the action required to avoid disaster. There wasn’t time to consult or refer the decision to senior managers. When the train divided, the indications on the panel could initially have appeared to be a track circuit failure, but Bill quickly identified that the ‘broken’ indications were in fact moving and that the train was divided, with the rear running freely on a steep decent towards Carlisle.

His responses of being calm under pressure, attentive, and assertive, are today classed as non-technical skills. The non-technical skills training, coaching, and assessment which is now in place is something that would have been unheard off in Bill’s day. The industry has also made massive improvements with counselling support.

The freight route around the station was unavailable for months due to the damage, and, in December 1985, the decision was taken not to restore the route. Signalling changes at Citadel station were made to facilitate all freight traffic passing through the station. The stub of the Goods Avoiding Line from Bog Junction was retained as a siding for a time to serve the Metal Box Co’s works at James Street. The remaining three spans of the bridge were demolished in 2008 and, in recent years, the stone piers have been removed to improve flood prevention measures.

Today, the old rail freight route is part of the Cumbria Way. You can still see the old bridge supports when walking along the pathway and, if you look at some of the flood defence fencing by the path, there are some images, including of signal levers, as a tribute to the near disaster on 1 May 1984.

Many readers may not have heard of this incident, but had the 10 wagons of dangerous chemicals thundered at over 60mph into a passenger train in Carlisle station, the date would be very well known in the industry.

Thanks to the public artwork on the route of the former Carlisle Goods Avoiding Line, and the commemorative plaque in the waiting room close to platform 6 at Carlisle Citadel station, Bill Taylor’s actions will never be forgotten. David is now in discussion with an operator to name a locomotive after his father as a further tribute.

With thanks to David Taylor, Gwyn Jones, Stuart Palmer, Mike Lamport, and Ken Harper for their help with this article.

Lead image credit: Cumbrian Railways Association